by Aaron Wilder, Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Roswell Museum

© Roswell Daily Record

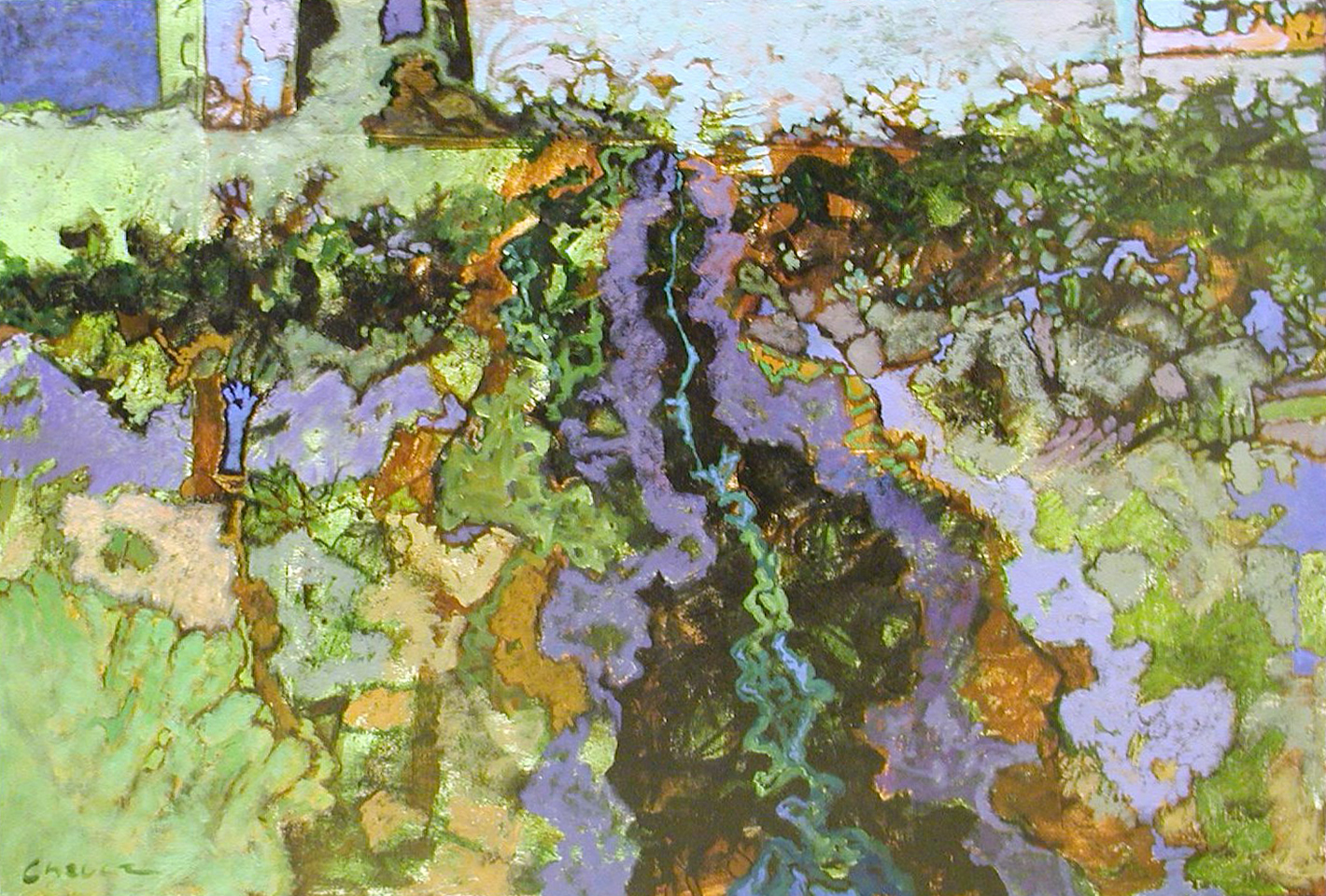

“Gunnison” by Edward Chávez, 1976, acrylic on canvas. Gift of the National Academy of Design’s Henry Ward Ranger Fund, Roswell Museum collection.

The last column from the Roswell Museum was In View: Mary Peck’s ‘Spaces in Between', published in the Roswell Daily Record on Oct. 20. This was written and submitted the previous week and was published the day after Roswell’s tragic flood. Located near the Spring River, the Roswell Museum was devastated by the flood. The waters reached nearly six feet inside the museum and damaged at least half of the 12,000 collection objects. A majority of the objects that were directly impacted by the floodwaters were sent to The Conservation Center in Chicago for evaluation and restoration. Additional items will be sent to specialty conservators.

Despite the museum facility being closed, we want you to know we are still here, and the staff is working behind the scenes on conservation efforts. While we are displaced, we are thankful to the Roswell Public Library for hosting our recently resumed “Second Saturday” community art days, to Bone Springs Art Space for presenting art classes to ensure the museum's previous students have offerings and to the Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art for hosting Roswell Artist-in-Residence exhibitions and artist talks. We’ll be rolling out other community and virtual initiatives over the coming months.

In our resumed column, we will be focusing on artworks that have remained here in Roswell in temporary storage. We’ve changed the column’s name to It’s Your Art as a reminder to the community that our collection is your collection and is being cared for even while it isn't currently viewable in person.

For the first iteration of It’s Your Art, I want to focus on the painting Gunnison by Edward Chávez. This artwork was on display at the time of the flood in the permanent collection exhibition, Here & Near: Surrounding Brilliance. Because the exhibition was hung “salon style” with works displayed from floor to ceiling, Gunnison was just above the floodwaters.

Born in 1917 in Ocaté near Wagonmound, New Mexico, Edward Chávez was one of 10 siblings in a family of sheep herders. His mother’s ancestry was from generations of families based in Taos, and his father’s was from Mexican immigrants. Chávez was still quite young when the family relocated to Colorado. As Stan Cuba wrote in an undated statement for David Cook Galleries, “An unusually hard winter wiped out all the family’s livestock and assets, necessitating relocation to Red Lion in northeastern Colorado, where the family earned a meager livelihood working in the local sugar beet fields.” Because he wasn’t able to speak English, Chávez faced discrimination from both educators and fellow classmates.

In a 1964 interview with Joseph Trovato for the Archives of American Art, Chávez explained he’d been painting since 1936 and that he was an apprentice to artist Frank Mechau on murals for the Treasury Relief Art Project, a federal program funding the decoration of government buildings. Soon after, Chávez was commissioned to create his own murals under the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federal agency funding public projects during the Great Depression. WPA-funded murals intended to show activities in the community as a way of inspiring hope for a better future. Chávez completed murals at post offices in Glenwood Springs, Colorado; Geneva, Nebraska and Center, Texas, as well as at Western High School in Denver, Colorado. His painting style employed in these murals is described as “American Scene painting,” depicting activities of everyday local life where subject matter can be described as “realistic.” In the chapter “Painting His Nostalgia: Exile, Memory, and Abstraction in the Work of Edward Chávez” in the University of Oklahoma Press’ 2015 book, A Contested Art: Modernism and Mestizaje in New Mexico, Stephanie Lewthwaite wrote, “The WPA was Chávez’s training ground in terms of artistic vision and personal growth … . Chávez’s mural commissions … were received warmly by the local community, although he recalled some residents … expressing concern that the figures in his mural … appeared to be of Mexican origin.”

Post-WPA, Chávez became a war artist and correspondent during World War II. About this, Cuba wrote, “He was inducted into the U.S. Army and (was) initially stationed at Fort Warren, Wyoming. For its Service Club, he executed … a large egg tempera mural on plywood … , as well as several other murals at U.S. Army locations.” Chávez’s watercolor painting “Convoy Practice” won third place in a LIFE Magazine competition. After the war, he settled in Woodstock, New York.

Chávez’s WPA experience enabled him to successfully transition from a public muralist to an artist with a gallery career. Cuba wrote that in 1947, “Chávez received several awards for his work, indicative of the recognition accorded him soon after settling in the East: Pepsi-Cola’s Fourth annual Exhibition — ‘Paintings of the Year,’ Associated American Artists Lithograph Competition, and the Albany Print Club. In 1948, Abbott Laboratories commissioned him to do a series of paintings on the state of American Indian health and medicine … His paintings were later exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution.”

In the 1964 interview, Chávez explained, “The four-year interval of the World War did create a bridge in the direction of my work. And I think immediately after coming out of the army, it began to evolve into more abstract work.” Exposure to art in different countries further impacted Chávez’s post-war work into an abstract trajectory. In 1948 he received the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award for travel to Mexico, and in 1951, he was the recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship to paint in Florence, Italy. Chávez is quoted by Cuba as saying, “I must always begin with very definite subject matter, something I have seen or felt or experienced. (My painting), although abstract in style, is also based on my personal experiences with nature.” Cuba continued, “Although he spent the last fifty years of his professional career based in Woodstock, New York, he primarily drew upon the imagery of his native New Mexico and the Rocky Mountain West, where he had spent the first half of his life. In the summers he traveled to New Mexico, Utah and Colorado, absorbing and sketching the landscape. It became the subject of his strong, bright abstract paintings.” Chávez’s 1976 painting Gunnison in the Roswell Museum’s collection is inspired by and named after the river carving through the steep walls of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park in western Colorado.

Lewthwaite wrote, “Since his childhood in the beet fields of eastern Colorado, Chávez had experienced social marginalization and discrimination as a mestizo subject tied to a family life of migrant labor. The condition of in-betweenness, of belonging and unbelonging, was intensified by Chávez’s departure from the Southwest and by his exposure to the competitive and often discriminatory realities of the art worlds in which he circulated. In later years, Chávez grew reclusive; he ‘withdrew’ from exhibiting much of his work and took to destroying or painting over his canvases.” The artist passed away in 1995.

Please stay tuned for more from the Roswell Museum. We appreciate the outpouring of support from the community during our closure. And remember, It’s Your Art.

For more information about the Roswell Museum, visit roswellmuseum.org.