The Roswell Museum

proudly presents

A Solo Show Featuring Artwork by Jane Abrams at the Roswell Museum, Curated by Aaron Wilder

Jane Abrams

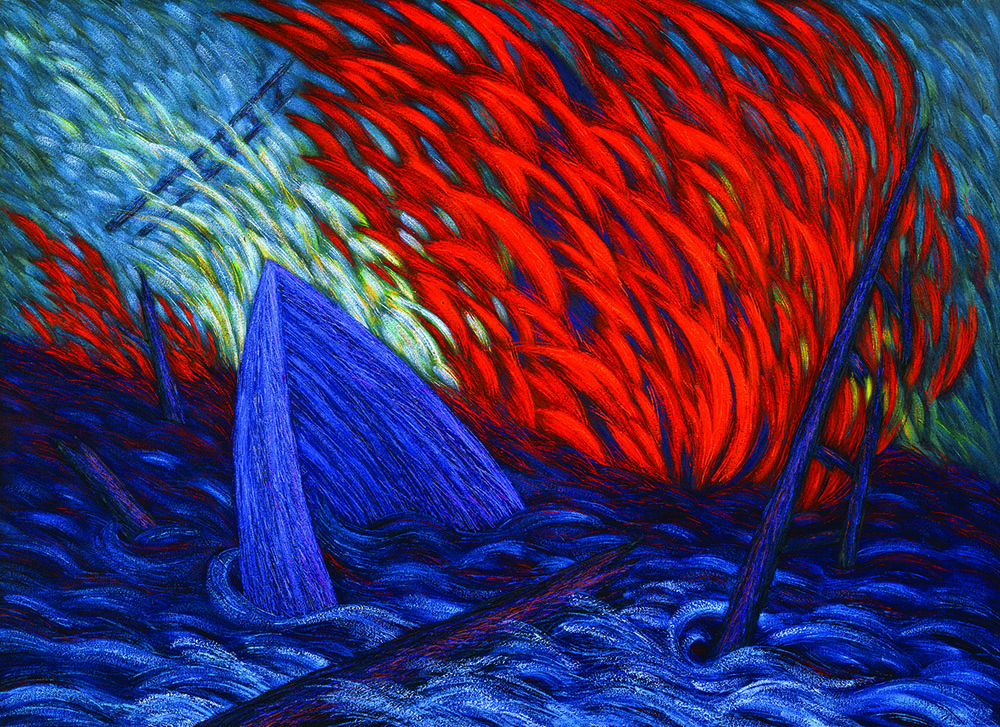

Clara's Boat/Fire on the Water, 1985

Oil on Canvas

Courtesy of the Artist and New Concept Gallery

August 3, 2024-January 12, 2025 (ended early due to October 2024 Roswell flood)

Opening Reception: Friday, August 2, 5:30-7 p.m.

Donald B. Anderson Gallery

1011 North Richardson Avenue

Roswell, NM 88201

The Roswell Museum celebrates the career of trailblazing artist Jane Abrams. The exhibition Jane Abrams: Fire on the Water showcases the artist’s painting, printmaking, and sculpture from 1968 to 2022. Subject matter ranges from landscapes of her travels and around her home in Los Ranchos Village near Albuquerque to the landscapes of her mind and spirit. The literal and symbolic themes of fire and water recur over the course of more than 50 years of art making. Abrams was a 1985-1986 Roswell Artist-in-Residence and broke barriers as the first woman to be a tenure-track professor in the art department of the University of New Mexico (UNM) where she taught 1971-1993.

Born in Eau Claire, Wisconsin in 1940, Abrams would go on to achieve undergraduate and graduate degrees at the University of Wisconsin-Stout in Menomonie in 1962 and 1967, respectively. She went back to school later and received a Master of Fine Arts degree at Indiana University in 1971. It was printmaking, predominantly intaglio, that Abrams focused on in her MFA program and it’s the artistic medium that took her to UNM. Even though the building she taught in was fairly new at the time, its poorly designed ventilation system would become another barrier. Printmaking requires the usage of chemicals which can take an irreversible toll on one’s health. In a 2001 article by Wesley Pulkka in The West Side Journal, Abrams was quoted as saying “From all those years of exposure to chemicals… my body was rebelling. My vision was blurred, and my fingertips were numb. After visiting several doctors and neurologists, I was told to quit studio work. That wasn’t an option, so I began looking for an alternative.” This confrontation with a new barrier led the artist to two areas that would ultimately transform her life and artistic practice. The first was ayurvedic medicine, which led her on a non-western healing journey through today. In Pulkka’s article, Abrams is quoted as saying “I walked into the [Ayurvedic] institute [in Albuquerque] and it was all incense and non-Western culture. Vasant [Lad] started with herbal treatments, and I started feeling better right away.”

The other direction of transformation was specific to the medium around which she centered her artistic practice. As Abrams explains in her 2021 book, Searching for Beyul, produced by New Concept Gallery in Santa Fe, “I was awarded the generous Roswell, New Mexico Artist Residency, also based on my work as a printmaker. The Roswell Grant provided a yearlong, all-expenses-paid ‘Gift of Time.’… The acceptance of the Roswell Grant and the move to a new studio in Roswell was to give me an opportunity to work away from the toxic environment at UNM. However, I soon discovered that even working in the new space and outside, the acid fumes and solvents were continuing to cause physical problems… It was clear to me I was unable to be in any contact with acid and solvent fumes without rekindling the respiratory difficulties… The generous patron of the Roswell Grant got wind of the problems I was having and immediately encouraged me to order a year’s worth of traditional oil paint, canvas stretchers and brushes… I found I could work safely without harsh chemicals and the most liberating of all was that my work was not restricted to the size and shape of paper. This began my life as a painter.”

Abrams needed time away from teaching to adapt from printmaking to painting as her primary medium and the year in Roswell provided such an opportunity to make these changes. Her time in Roswell also had an impact on the subject matter of her art. In a 1993 article by Lis Bensley in The Santa Fe New Mexican’s Weekly Arts & Entertainment Magazine, Abrams is quoted as saying “I would spend hours walking at dawn through the pecan orchards there. It was just at that time when light started hitting the trees. As I watched, the light became a rhythm, raking shadows through the trees, shifting in tone. Those images really struck me and I began painting those experiences.” An exhibited painting from the museum’s collection, Days End in Fire/West of Montana, exemplifies the fiery rhythm of light she experienced in the pecan orchards while in Roswell. And with her focus shifting to painting, she had ample time to explore different materials to adequately convey the feeling of experiencing this light. In addition to oil paint, she successfully achieved this through introducing beeswax and pigment. In an undated statement written by the artist in the museum’s archives from when she was here on the 1985-1986 residency, Abrams said “The trees form endless rows… but there is an end and at that end there is a light and with the light there is a change and with the change a new road… once on that new road I will arrive at a place I have never been.”

The artist’s process is intuitive. Abrams follows an inner compass, guided by procedural ritual, to arrive at a finished work of art. “It’s a little ceremony,” the artist is quoted as saying in a 1993 article by M.S. Mason in The Christian Science Monitor, “to close all the books and stack them up neatly and coil up the hose on the vacuum cleaner, sharpen all the pencils, and get everything neat. And then I may have three large blank canvases out. I love to sit in my grandmother’s rocking chair and look at the canvas… I’ve been reading and thinking and responding and feeling… That colors my reaction to the surface of the canvas. There might be a shadow or a mark on the canvas that will set me off. And something will occur.” In a 2007 catalog for her solo exhibition at New Mexico State University (NMSU) Art Gallery she adds, “An image appears on the canvas before the brush meets the surface.”

The materials Abrams uses provide both a pictorial depth and a visibly sculptural surface. In that 1993 article, Mason explains: “Abrams’s method – a modification of the ancient encaustic painting technique – incorporates wax into the oil paint. The resulting luminosity and density of impasto lends an almost sculptural presence to the painting.” Abrams’ intent is to seduce the viewer from afar with the painting’s luminous colors, reeling them in to see its complexity up close in not only the topographical nature of its surface, but also as a window into the artist’s worldview. In Bensley’s 1993 article, the artist explains “I want the work to exist on a physical level with a color that pulls you close and a surface you want to touch… As that sinks in, then I like to play with the conscious. With interesting twists.”

The careful, subtle twists Abrams builds into her compositions rely on the conventional beauty of her colors, materials, and subject matter to draw the viewer in; to beckon them into her worldview. In Searching for Beyul, Abrams wrote, “The familiar fields, desert, acequias and rivers near my home have readily provided a rich source for my paintings. Over the years I have also, through travel, found inspiration in my sensory wanderings around the globe. I have walked in the ancient ruins and jungles of Mexico and Central America, cloud forests in Guatemala, along rivers in India and in the mountainous regions of Thailand and China.” These gorgeous landscapes lead us on journeys to a multitude of destinations. Bensley wrote of the possible destinations in the 1993 article by saying, “there are secrets intertwined in Abrams’ lush vegetation. Political secrets, spiritual secrets, whisperings of deep, unexplored inner mysteries. This is a world of subterranean richness.”

The mysteries of the personal, or spiritual kind in Abrams’ work can be observed in the details of the landscapes and in the varying approaches to metaphor in symbols she depicts. In an essay in the catalog of Abrams’ 1991 solo exhibition at Indiana University, Kathleen Shields wrote, “perhaps more than images of the places she visits, they are images of her state of mind, reflections on her place in the world.” The artist’s own secrets are hidden in these vistas and they offer an opportunity for viewers to see connections to their own experiences through Abrams’ visual language. In the catalog of her 2007 solo exhibition at NMSU, she shares, “Encounters from my dreamspace end up on the tip of my brush… Meeting red in a dream is like meeting no other red on earth… the same can be said of fire, water, rock, or rubble… I work from a place where dreams and memory fuse into color, light and form. The volcano… a dangerous scientific phenomenon… swollen earth, building pressure and a thrust of energy from the deepest root chakra of the earth… a caldron of fire… the earth’s pelvic bowl… the airborne ash from the cremation piers landing softly on my face… the life that exists on the edge between the fluidity of the ocean and the stability of the land…the storm boiling overhead… It is not the storyline that works its way into my painting but the juicy, emotional sentience of fire, water, light, color, texture, gesture and all the abstracted essences from which paintings are made.”

The elements of fire, water, and beyond in Abrams’ visual vocabulary can be seen across mediums. In addition to the artist’s roots in printmaking and her current focus on painting, wooden sculptures, predominantly made in the 1990s, are also exhibited. About this, Bensley wrote in 1993, “She’s also started working with wood, an experience she says brings her back to her childhood… ‘I began carving out wood, then painting it,’ she said. ‘My father had a woodshop where he used to go and hide from my mother. When I was young I’d accompany him. I always loved the smell and feel of wood.’” In these wood sculptures as well as the work in other mediums exhibited, there are particular symbols of primary importance to the artist’s own personal history repeated across compositions. In the 1991 Indiana University exhibition catalog, Shields wrote, “Around 1987, having returned to Albuquerque, Abrams began to insert symbolic images of boats, ladders, fire and flying birds into more imaginary landscapes. Empty rowboats… may be tossed by churning water or upended on dry land; ladders reaching skyward span hot licking flames. These images seem to signify transformation or passage through states of upheaval, engulfment, breakage or destruction, and release. Indeed, the series of ‘Clara’s Boats’ may be seen as witnessing the voyage of Abrams’ mother who passed away during this time.”

In the undated statement from her 1985-1986 Roswell residency, Abrams attempted to come to terms with her mother’s declining health by expressing, “Her face reflects strain as her fractured mind searches to place me somewhere within her eighty year framework. The relationship has changed; it is all new, new rules, new dialogue, new responses, new distance, and a mandate to be a different person in her presence. Tomorrow I may once again be her daughter… but today my mother doesn’t know me. I listen for the last time to the sound of the furnace going off then coming on. I feel for the last time the warm breath of air circling across my room on the upper floor. My thoughts are punctuated with the memory of her chronic morning cough, the militaristic click of her heels on the kitchen floor and the systematic slamming of the door to my upstairs sanctuary, signaling that I have been dreaming too long. Tonight the living room is illuminated with the lamps she never lit… they fill the rooms with a mellow nostalgic glow of the forties. I continue to sort through her possessions, making instantaneous decisions about the fate of eighty some years of saving, collecting and caring.” The iconography the artist uses to process her complex feelings around her mother’s death, provide opportunities for us to relate our own internal landscapes to Abrams’ work.

In Searching for Beyul, Abrams wrote “I have continued to enjoy how landscape painting is as much a revelation of the facets of the mind, as it is an exploration of the wonders of the natural world.” The Roswell Museum’s exhibition Jane Abrams: Fire on the Water is a celebration of the artist’s 50+ years of artmaking, exploration, reinvention, and impact on younger generations. For more information about the artist, visit janeabramsstudio.com.

Jane Abrams has exhibited her work across the United States and internationally. Her artwork is included in several public collections, including the Albuquerque Museum, the Museum of New Mexico, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. In addition to being a 1985-1986 Roswell Artist-in-Residence, other residencies include those at Anderson Ranch in Colorado, the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Nebraska, the Everglades National Park in Florida, Fundación Valparaíso in Spain, the Julia and David White Artist's Colony in Costa Rica, the Robert M. MacNamara Foundation in Maine, and the Tao Hua Tan International Artist Retreat in China. Abrams has received several prestigious awards. In addition to two NEA grants, other accolades include grants from the Ford Foundation, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and the Tamarind Institute.

Supplementing artworks from the Roswell Museum’s collection, most of the exhibited works are loaned directly from the artist’s studio. A momentous thank you is owed to Jane Abrams for collaborating on this exhibition, for sharing her work with the Roswell Museum’s audiences, and for inspiring all of us with her resilience, creativity, and dedication to her craft. A debt of gratitude is owed to Aaron Karp for his decades of support of Abrams’ practice as well as for his assistance with this exhibition. Thanks is owed to Boo Abrams-Bickel, Foster Hurley, and the Albuquerque Museum for loaning additional works for this exhibition; to the City of Roswell and the RMAC Foundation for their financial support; to Patrick Carr and Troy Buchleiter for sharing photographic documentation of Abrams’ works; to the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Foundation for being a supportive partner; and to Agustín Pozo Gálvez for his translation of text about the exhibition to Spanish.

Curated by Aaron Wilder