The Roswell Museum

proudly presents

Patrociño Barela: I Stand On My Own Feet

A Show Featuring Artwork from the Collections of the Albuquerque Museum, the Harwood Museum of Art, the National Hispanic Cultural Center, and the Roswell Museum by Patrociño Barela, Curated by Aaron Wilder

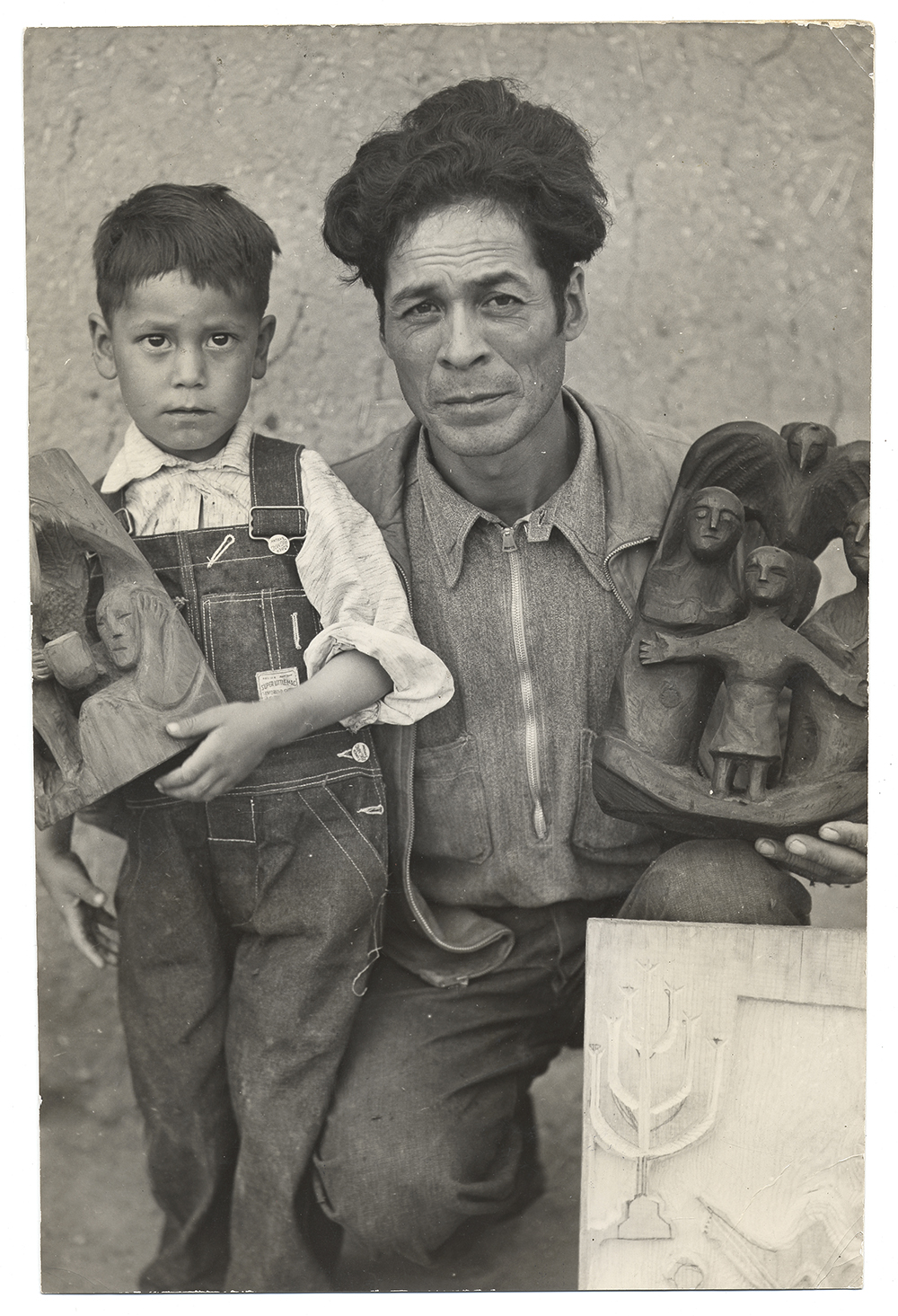

Patrociño Barela & son with several sculptures, Circa 1936, Unidentified Photographer, Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

August 12, 2023-February 11, 2024

The Roswell Museum

Founders Gallery

1011 North Richardson Avenue

Roswell, NM 88201

The Roswell Museum pays homage to one of the most legendary, yet underrecognized creators of modern art in New Mexico’s history. Patrociño Barela’s short, but prolific career transforming chunks of wood into abstracted sculptures touching on both spiritual and secular themes is celebrated in the first of a series of exhibitions exploring the output of groundbreaking artists who made significant artistic contributions to our region. A commonality between Patrociño Barela and the Roswell Museum is our shared connection to the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a US federal government agency designed to support the arts during the Great Depression. The creation of the Roswell Museum was financed, in part, from WPA support as a federal art center in 1937. By then, Barela was not only already a WPA artist, he had also already received early acclaim for his WPA-funded sculptures exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In the 1996 book Spirit Ascendant: The Life & Art of Patrociño Barela, artist Edward Gonzales and curator David L. Witt wrote about the artist, “A man of humble origins, Barela overcame immense hardships to create some of the most powerful art to come out of New Mexico.” The exhibition Patrociño Barela: I Stand On My Own Feet is on display in the Roswell Museum’s Founders Gallery from August 12, 2023 to February 11, 2024.

Like many details about Barela’s history, his exact date of birth is unclear. Based on many accounts of those who knew him in his lifetime, he’s estimated to have been born in Bisbee, Arizona sometime between the years 1900 and 1904. In the El Palacio Magazine winter/spring 1996-1997 article Patrociño Barela: Expressionist Carver, Carmella M. Padilla explained Barela was born “to Manuel and Julia Barela, an itinerant Mexican laborer and his Mexican-American wife. In 1908, after the deaths of Julia and their infant daughter, Manuel moved Patrociño and his elder brother, Nicolas, north to Taos in what was then the Territory of New Mexico… after arriving in Taos, Manuel turned from sheepherding to a new vocation as a curandero, a traditional herbal healer.” Allegedly, Manuel became sought after for his cures for a range of ailments including burns and gunshot wounds by mixing his own homeopathic remedies with medications commonly available from local drugstores. Padilla continued that Manuel soon “traveled the region to treat the sick. At home, however, Manuel was a physically abusive father who showed little concern for his sons. Patrociño was twelve when he packed up a few belongings and left… his first journey came to an end in Denver when he was discovered unconscious by a policeman and placed into foster care. He lived a brief time with an African-American family who taught him some basic English before he continued on his way.” It is thought that in some of his later sculptures, including Untitled (Portrait of a Black Man), can be seen as odes to this nurturing family and the kindness they showed him. For the next twenty years, Barela roamed nomadically across Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming following any opportunity for work that came his way.

Patrociño Barela, Untitled (Portrait of a Black Man), Circa 20th Century, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

Much later, Barela told Taos Modern Kit Egri about the earliest stages of his life by saying “I was born… in Bisbee, Arizona, where the old mines are. There were two children. My mother died when I was four and my sister before that. My father left Bisbee and came to Taos – he travel a lot. Manuel Barela, doctor of wild weeds. He don’t read or write but the records in Santa Fe prove he was a doctor of wild weeds. I had no school. In 1931 I started to carve though I cannot read or write my whole first name.” Because of this and other reasons, there has been ambiguity as to the spelling of the artist’s first name. The variations “Patrocino,” “Patrocinio,” and “Patrociño” have largely been used interchangeably. For the purpose of this exhibition, the Roswell Museum refers to the artist consistently as “Patrociño Barela.” In a 1956 interview with Lenore G. Marshall for Arts Magazine, Barela shared additional information about his early life and how he got his start with woodcarving: “My daddy he sent me to watch goats in the hills. I go here, there, nine years, dig potatoes, coal mines, work in WPA, haul dirt, ate breakfast, went out. One day the priest showed me old figure of Saint Angelo, broken, he say, ‘Pat you think could be fix?’ I say, ‘Padre, we can try.’ We work all night and fix. That santo was done in joints, pieces put in with pipe. I came home and lay on bed and think how you can make it so it is in one piece. All one. I can not sleep all night. Next day after work I eat supper quick, go out where I got pieces of wood. I choose some with no knots, and I begin with pocket knife. My wife call, you no going to sleep? I no answer her.”

As with his year of birth and the spelling of his first name, how Barela got his start with carving is unclear despite what he told Marshall in 1956. In the Journal of the Southwest issue of spring 2010 in an articled entitled Modernity, Mestizaje, and Hispano Art: Patrocinio Barela and the Federal Art Project, Stephanie Lewthwaite wrote “According to one account, Barela learned how to fix wood as an itinerant laborer and applied this knowledge to repairing a santo in 1931. Another version claims that witnessing a friend fixing a bulto inspired Barela to carve his own figures, which he then sold in the local store.” In a close-looking guide accompanying the display of one of Barela’s sculptures, the Ackland Art Museum explains “Santos are traditional representations of saints or other religious figures usually through wood carvings in the round (bultos)… Barela himself was a self-taught maker of santos. This tradition was brought to the American Southwest by Spanish colonists of the seventeenth century.” In the San Francisco Weekly issue of April 14-20, 1999 an unidentified author explained in the article Saints Be Praised that “Barela was not a practicing Catholic and had no formal artistic training, so he approached the santero practice in a whole new way, stripping the form of its traditional religious elements and carving solid sculptures with no appendages to break off.” In Spirit Ascendant, Gonzales and Witt add “Barela’s work required considerable knowledge of religious iconography; and the research necessary to complete these images contradicts Barela’s illiteracy as well as his lack of religious background or interest in attending church functions.”

Patrociño Barela, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Circa 1950, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

Gonzales and Witt use Barela’s sculpture Expulsion from the Garden of Eden from circa 1950 to illustrate the level of abstraction the artist was employing in the style of his works at the time: “It is a sculpture of major size for the artist, carved from an unusually shaped stump. The carving achieves a balance between the natural shape of the wood and the figures that appear to grow from it, as Barela allowed the wood to express itself. The two flanking figures, left and right, are Adam and Eve. The expulsion from the garden is characterized by three symbols: the serpent head between the couple on the left, the bestial pig-headed figure in the center, and the hidden face in between, representing an avenging angel or God the Father. Barela’s reliance on abstract forms makes this work one of his monumental achievements by balancing his lifelong interest in religious subjects with his passion for personal expression. In this work Barela reached new heights as an expressionist artist.”

Traditionally, bultos are made by joining together multiple pieces of wood that are carved individually and are then painted once assembled. Each of Barela’s bultos are one solid carved piece of wood, such as cedar. Not using paint, most of his sculptures showcase the natural color of the chosen wood as well as any other unique features such as knots. In Spirit Ascendant, Gonzales and Witt state “Barela carved a few works in cottonwood and in woods which we did not identify, possibly including Ponderosa pine and Engelmann spruce. However, the vast majority of his carvings were from juniper wood, or cedar, as the various juniper species are known throughout the West.” Patrociño Barela’s sculptures are “in the round,” meaning that viewers can only gain an understanding of an object’s full significance by seeing it from multiple angles. In a July 1964 interview with Sylvia Loomis, Barela explained each of his carved sculptures are unique: “I don’t copy… I do my [i]magination and so-and-so feeling, you know. I make one figure this side, another one over here, to fill ‘em up, the piece of wood. It depend on the size, but I do this on cedar because I like better for the natural color.” In the Presbyterian Life issue of February 15, 1968, Barela’s friend Mildred T. Crews wrote in the article Patrocinio Barela: Taos Woodcarver that the artist “rarely, unless working on a specific commission, plans his pieces, but allows them to evolve from the shape of a particular chunk of wood, being dictated by its shape, grain, and knots. He did not put any finishing solution or wax on the carvings, and they retain the cedar fragrance for years.”

Patrociño Barela, Untitled (Sinners in the World), Circa 20th Century, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

After his nomadic roaming in his teens and twenties, chasing what work he could find, Barela moved back to the Taos area in 1930. Shortly thereafter, he met and wed the widow Remedios Josefa Trujillo y Vigil, a woman who already had four children. The couple would later have an additional three children. In the Roswell Daily Record issue of January 26, 1997, then Curator of Education at the Roswell Museum, Dr. Michael J. Riley, wrote in the article Patrociño Barela exhibit opens, “Living in poverty, they barely made ends meet until Barela found work as a teamster with the Depression era Federal Emergency Relief Administration.” For a short period of time, Barela used his horses and wagon to haul dirt and supplies and other services for the government initiative before he was offered a unique, albeit lower paid opportunity to pursue his art with the WPA’s Federal Art Program (FAP). Lewthwaite explains, “In tandem with Taos artist Walter Ufer, local WPA official Ruth Fish discovered Barela’s work, either at the local store or through Barela’s direct attempts to sell his sculptures, and hired Barela onto the FAP at the end of 1935 at the paltry sum of $54 per month.” When asked about Fish by Loomis in the 1964 interview, Barela replied “That lady is the manager of that office here on the WPA, and I make a few pieces, I believe about two or three, and I put ‘em on (what) used to be store—Birch’s—Albino Birch—so I ask him if I can put ‘em on the inside of the store for showing the people, so the people can see it, and I work on the WPA, so he say, ‘Yeah, bring it over.’”

Due to the fact that Barela had never learned to read or write, he had difficulties understanding the bureaucratic paperwork the WPA required contracted artists to complete in order to be paid. The workaround solution was that WPA officials gave him a sheet of paper filled with empty squares. To record his daily work, he was asked to write in a cross in the box corresponding to each day. Loomis also asked about this in the 1964 interview. Barela explained how this worked by saying “I get them three witnesses, and go back and give this paper to that lady, that Ruth Fish, and she send it, and in about three weeks they call me again, and they give me a great big envelope with the papers, and they told me, ‘Every day you work eight hours and make a cross in one of these squares,’ because I tell them, ‘I don’t read, I don’t write,’ and they say, ‘You just make a cross in one of these squares…’” While it was Fish who was the first WPA official to recognize Barela’s artistic potential and his good fit with the ethos of the FAP initiative, it was ultimately Russell Vernon Hunter who made the artist’s participation in the project possible. After Fish brought Barela’s work to Hunter’s attention, he immediately recognized the artist’s talent.

Patrociño Barela with four wood carvings and his little son, Circa 1936, Unidentified Photographer, Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On October 30, 1935, Hunter was appointed the Director of the New Mexico division of the FAP and he remained in that position for the entire duration of the program until it was discontinued in 1943. In Spirit Ascendant, Gonzales and Witt cite official WPA records in how Hunter perceived Barela in their first meeting: “He is very attractive, with very large piercing, but friendly eyes, very dark skin, the brown of which is deepened and enhanced by years of exposure to the bright western sun; his hair is thick, black, and extremely curly. His features are regular and strong, and his hands are firm and have a line of delicate artistic tendency that is not compatible with his brawny arms and wide shoulders.” Barela received much needed encouragement for his artistic practice from Hunter during the WPA years. Aside from general WPA affiliation, the Roswell Museum and Barela also share direct connections to Hunter. After the end of the WPA, Hunter would later become the Director of the Roswell Museum.

If Barela found in the WPA a much-needed boost to his artistic passions, Barela was also at least as valuable to the WPA. Lewthwaite writes “Barela became the New Deal’s ‘everyman’—the archetypal universal laborer-cum-artist who symbolized FAP’s drive to democratize art. Barela was untrained—‘an instinctive artist without education’ whose work was rooted in the community, according to FAP National Director Holger Cahill.” The FAP recruited artists nationally and not only paid them, but also provided unprecedented public exposure to their art through public projects such as murals and also to display their work in public buildings ranging from museums to post offices. In Spirit Ascendant Gonzales and Witt wrote “To introduce the novel concept of government support for the arts, the best Federal Art Project artists were shown at the Museum of Modern Art. Of the thousands employed, 171 artists were selected with 400 works for the museum show. Barela, represented with eight carvings, had more pieces in the show than anyone else.” As a result, Barela’s name and overwhelmingly positive reviews of his work were published in national and regional publications coast-to-coast. Reflecting on this in the 1964 interview with Loomis, Barela said “they were sending some pieces to the White House, and one piece of board—they call him ‘The Shepherd’—and about two years later, [Russell] Vernon Hunter told me that ‘Shepherd’ is still in the White House. The rest they go to New York. But it’s all over, all over.” This sentiment simultaneously expresses Barela’s awe at having his carvings displayed in elite institutions in places to which he’d likely never have the opportunity to go and his disappointment in his brief national fame ending so abruptly.

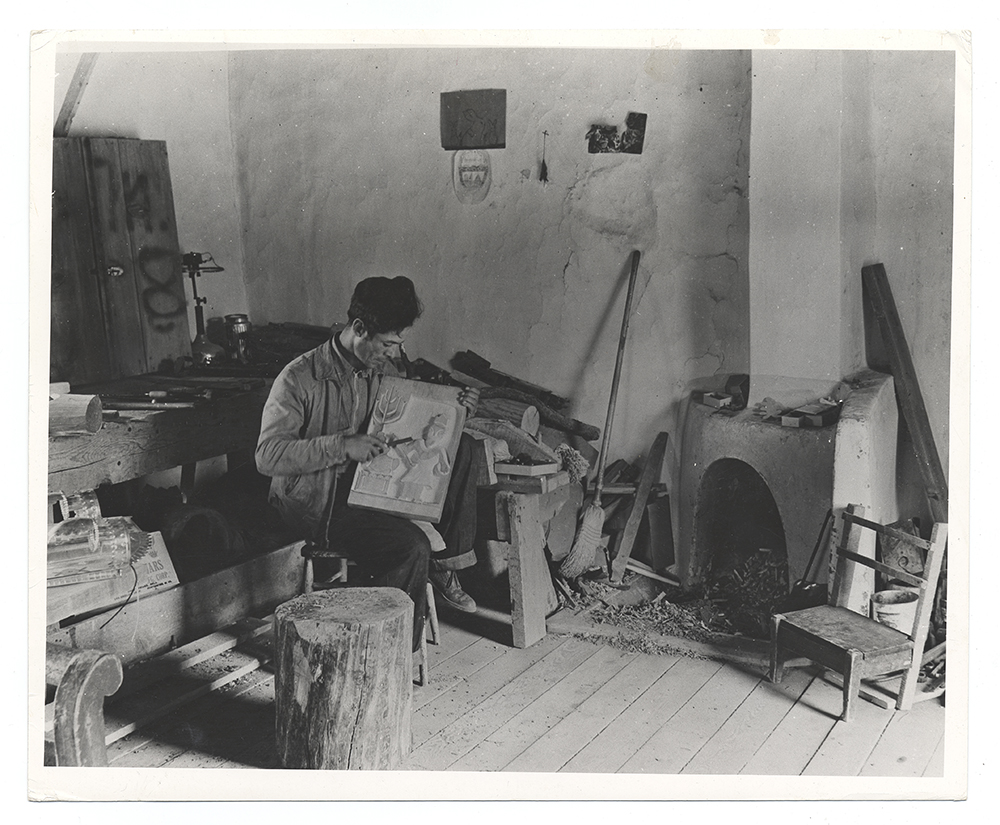

Patrociño Barela at work on a wood carving in his studio, Circa 1936, Unidentified Photographer, Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“Despite such high praise,” Dr. Riley wrote in 1997, “Barela’s career did not skyrocket. His lack of knowledge about the inner workings of the art world stood in his way. In addition, to ‘protect’ Barela from exploitation officials of the project isolated him from art dealers. Throughout the remainder of his life he never again showed in a major exhibition, and his triumph in New York faded into memory.” Padilla explains this a bit further: “The overwhelming praise for Barela prompted inquiries to [Russell] Vernon Hunter and Holger Cahill, the national director of the Federal Art Project, from commercial art galleries in New York interested in showing the artist’s work. Because Hunter feared that big city business dealings would intimidate Barela, quashing his artistic integrity and creative spontaneity, he discouraged Cahill against such a move; Cahill agreed. Barela apparently was never apprised of the New York offer, and he was never to be presented with such an opportunity again. ‘They thought they were protecting him because they thought he was a country bumpkin who would have been spoiled by the public eye, but I think they did him a disservice,’ Gonzales says. ‘Had they helped him show at national galleries, I think he would have made a better living and had a better life in Taos. He would have certainly been much more successful in the public eye.’” Instead of “protecting” him as they supposedly intended, Barela’s white WPA supporters effectively stole from him any opportunity to support himself financially from his artistic practice in the future. As Gonzales and Witt explain in Spirit Ascendant, “Ultimately, Barela was one of the last artists to be let go from the Federal Art Project; his contract was terminated in 1943. By then, Hunter’s actions to protect Barela from potentially unscrupulous New York art dealers had succeeded all too well—not only was Barela not exploited, he was forgotten outside of New Mexico. Although Barela did not stop carving, as a result of these circumstances, he never got a New York dealer in his lifetime. He went back to herding sheep.” Without financial opportunities to sell his sculptures, Barela returned to itinerant employment to support his family, often away from home, for a period of twelve years. This made it difficult for the artist to devote time to his artistic expression through wood carving.

In the mid-1950s, three of the strongest supporters of Barela’s artistic practice paid homage to him in a book. Poet Wendell Anderson, poet and printer Judson Crews, and photographer and writer Mildred Tolbert Crews produced the book Patrocinio Barela: Taos Wood Carver. About it Padilla said “All of his life, Barela had been branded with the stigma of being illiterate, but on the pages of the book, and in many other subsequent articles written by Crews, the artist’s words poured out like poetry.” One example provided the inspiration for the title of this 2023-2024 exhibition at the Roswell Museum. Barela is quoted as saying “Before idea come, I got my head, but no use; just sitting, dreaming all (the) time. When I find my head, a notion comes from the air. (This) is where I planted the future for me, which has been the art I discover. I put my right hand to my head, surprised. I stand on my own feet. I didn’t know I had those brains to develop such things as I have discovered for my future, so I planted that tree which you know is straight and full of life.” In addition to references here to the artist’s head, hands, and feet, the heart is also important and it is symbolized in many of Barela’s works. About one of his sculptures with a carved heart shape, the artist said “A good heart keeps you safe. When Christ traveled in those days there were no rifles or pistols to keep himself safe. Only a good heart.”

Patrociño Barela, Untitled (Three Faces with Heart) (detail), Date Unknown, Carved Wood (Cedar), Gift of Elizabeth and Jim McGorty

In addition to the traditional santos Barela made, it can be seen from the earliest of his carved forms that his own personal iconography was the focus. Barela created sacred and secular sculptures simultaneously. While more attention has been paid to his religiously inspired works, Gonzales and Witt noted in Spirit Ascendant that the majority of the carvings he produced throughout his life, based on their extensive research, were non-religious in theme: “Barela made a break from earlier New Mexican wood carvers, as well as his contemporaries, by working extensively with non-religious themes… No topic was off-limits, and he examined everything from the economic to the erotic. He was keenly interested in the irony of life, especially the desire and fear which surround marriage. His children were his great love, yet responsibility for his family carried with it a certain amount of terror for one who had grown up as an independent wanderer.” Humor was also expressed through Barela’s work. Gonzales and Witt give the following humorous example: “Chupa Puro (Cigar Sucker), created by 1956, is one of two freestanding figures that depict Barela’s friend and neighbor Toby Sanchez, who was given ninety days in jail for public drunkenness; Barela described the circumstances as follows: ‘My neighbor asks the judge for mercy but the judge waves his arm and says take him away. The judge is smoking a big cigar. Chupa Pur[o] the people call him when he is not around.’ Judge Flores was known in the community for always smoking big cigars, even in court. In the imaginative two-figure sculpture, Barela captures the moment when the arbiter of the court passes judgment on his unfortunate drinking buddy… The hapless defendant reels back in disbelief. The composition goes beyond mere narrative… Barela’s ultimate intent was a visual pun. When turned to its back, the carving of the judge, Chupa Puro, becomes a charon, a Spanish taboo word… Its English equivalent is ‘big prick.’ The obscenity is all in fun, a way of permanently overriding the decision of the court and cutting the pompous judge down to size.”

Patrociño Barela, Chupa Puro (Cigar Sucker), 1956, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

Universal themes of the human spirit are expressed in Barela’s works, including birth, aging, death, familial complexities, parental affection, and more. About his sculpture Hope or the Four Stages of Man, Barela said “Man is born and created by laws of nature, so he [is] born all by himself and then he hope for that hope he has been waiting, and then comes Number 2, which means it is a son which has been reproduced by him and it only half the man he should be, but then he grown up to a man and that signifies Number 3. Numbers 2 and 3 make a complete man and he grows up like the tree that is by his side—large and strong in life, full of happiness and full of hope. But then comes Number 4—that man is growing older, he has gone through life, he has worked and struggled, now he is old, tiresome, and weak. Same way with the tree by his side… A man lives four different kinds of life in his life; when he is boy and when he is a young man, and then middle man, and then an old man, and those have been my ideas to carve a Bulto so as to represent the life of man in these carvings.” According to Lewthwaite, “Barela’s work was deeply personal. But in referring repeatedly to his family life, Barela alluded to wider social themes, and to the ways in which migration and uneven economic development disrupted communal and individual cohesion.” In Spirit Ascendant, Gonzales and Witt add “Even in his early period Barela was concerned with family relationships in his art, both contemporary families and the Holy Family. This interest probably grew out of his lack of a cohesive family during much of his youth as well as his later experience as husband and father. The death of his mother, the difficult and sometimes brutal relationship he had with his father, and his isolation from society as a child left Barela in an emotional vacuum.”

The abstract nature of his work led to a level of ambiguity of any kind of implied statement in each work on the part of the artist. Lewthwaite said “Barela’s carvings evoked multiple meanings by blurring the distinction between the sacred and the secular, the communal and the individual, the family and the self.” This ambiguity is exacerbated by a lack of clarity about individual object titles and explanations from the artist of subject matter depicted in individual works. During the WPA years, Hunter reportedly said “it is exceedingly difficult for us to get titles for Barela’s work. He is often so inarticulate that a good Spanish interpreter cannot pass his ideas onto us. He speaks, apparently, of things which are hard to grasp; and since his work, which harks of the saints, does not abide strictly in the precincts of the church, the fathers cannot define them.” This lack of precise definitions is what makes Barela’s works so accessible and universally relatable. From Gonzales’ point of view “Barela tied into the primal reasons we are human. And as long as there is the slightest bit of humanity in this world, Barela’s work will touch people’s souls.”

Patrociño Barela, Arguments, Circa 1950s, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

Despite being robbed of the opportunity to support himself financially through an arrangement with a commercial New York gallery by his white WPA mentors, Barela continued creating works and trying to sell them until his final days. His friends and the few local collectors buying his works recalled that he did indeed sell some works directly to galleries in Taos. In many of their opinions, Barela sold his works at prices beneath their actual value, but they also acknowledge this was likely due to dire financial need. He was often remembered as stoic and his friends Judson and Mildred Crews and Wendell Anderson remembered him as “accepting adversity as a natural part of life.” In a review of an exhibition at the University of Arizona in 1961, Dr. J. Douglas Hale said this about Barela’s art: “How can we describe sculpture that is small, yet monumental; amusing yet dignified; naïve but sophisticated; undisciplined but showing the skill of a natively talented artist; happy but immeasurably sad… showing recognizable subject matter yet powerfully abstract; complex in conception but charmingly simple in appeal.”

On October 23, 1964 in the evening, Barela was carving in the shed he used as a studio that was approximately 100 feet from his family’s modest home. A little after 3:00am the next morning, Padilla explains “a fire had engulfed Barela’s wood-filled work place, consuming the structure, the artist’s tools, and the worn metal bed where Barela slept. There was much speculation about the cause, but whatever the circumstances Barela was dead.” In Spirit Ascendant, Gonzales and Witt discuss a couple of the possibilities of the tragic accident: “The fire may have escaped the stove while he was sleeping and exploded the nearby gasoline can, or perhaps Barela had awakened cold and attempted to restart the fire in the middle of the night, mistaking the gasoline can for the kerosene.” The artist’s eldest son, Luis Barela, Sr. is quoted in Spirit Ascendant as saying “He carved until he died… At the end he couldn’t see very good, but he could feel.”

Patrociño Barela, The Pain that Comes with Life, Circa 20th Century, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

As Barela’s artistic practice was difficult to categorize during his life, his legacy also eludes easy categorization. Even though he was an active artist for at least thirty years in the early to mid-twentieth century, many do not consider him a modernist with the likes of many of his contemporaries. The labels often applied to him, such as “folk,” “primitive,” “simple,” and “tribal” likely reveal the true, unacknowledged classist and racist sentiments of recognized modernist artists and the art world power players. From Padilla’s perspective, “Although Taos had by then earned international acclaim as a thriving artists’ colony, Barela generally was shunned by the local art establishment as ‘naïve,’ ‘primitive,’ ‘a folk artist.’ Barela’s Mexican-American roots made him an even less likely candidate for either the esteemed early-twentieth-century Anglo ‘Taos Society of Artists’ or the more recent modernist vanguard, the ‘Taos Moderns.’” Gonzales and Witt view this from a more nuanced perspective: “Barela can… be viewed as a self-taught modernist. His use of space clearly fits within the tenets of twentieth century modernism. His use of form bears favorable comparison with that of Henry Moore – who was one of his collectors.” Lewthwaite adds “Barela could be deemed a modernist on the basis that he influenced the Taos Moderns after World War II and exhibited alongside them at La Galeria Escondida. Barela certainly influenced sculptor Ted Egri, who used Barela’s sculptures for teaching his own students.”

The question of whether or not Barela can be considered a modernist artist in his own right may be unanswerable. However, his legacy of inspiring contemporary Hispanic artists is clear. Many young artists in the Taos area and beyond came to Barela’s studio while he was still alive, observing how he carved wood and looking up to him as a role model. Padilla has said of these young admirers “Their interest debunks the myth that Barela’s work was not appreciated by his own people, and when he died, praise from them, from other artists, and from art aficionados intensified as everyone remembered that Barela had been an artistic genius living in their midst.” In a spring 1999 Mexican Museum memorial statement about the artist, an unidentified author wrote “It was not until after his death in 1964 that his works were shown in solo exhibitions, primarily in New Mexico. A 1980 Santa Fe retrospective played a key role in renewing interest in Barela’s work, and his inspiration began to be felt among many young Hispano artists and scholars in the region. In the 1990s, Barela’s renown began to extend beyond New Mexico. Already included in the collections of New Mexico’s major museums, Barela’s work began appearing in important public and private collections in Texas, Arizona, California, Colorado, New York, and Washington, D.C. In 1995, Barela’s work was included in Modern Figure in American Sculpture, a traveling exhibition organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A 1996 exhibition and publication, Spirit Ascendant: The Art & Life of Patrociño Barela, further broadened interest in his work… contemporary artists influenced by Barela, includ[e] Luz Martinez, Luis Tapia, José Benjamin Lopez, and Barela’s grandsons, Luis Barela, Jr., Carlos E. Barela, and great-grandsons, Eric and Daniel Barela.”

Patrociño Barela, Family Tree, Circa 20th Century, Carved Wood, Anonymous Gift in Honor of Virginia & Edward Lujan, Photograph by Addison Doty, Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum

Barela’s work has been exhibited at venues including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Alabama, the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, the National Academy of Design in New York, Rod Goebel Gallery in Taos, and the Wichita Museum of Art in Kansas, among many others. His work is included in many public collections regionally and nationally, including the collections of the Albuquerque Museum, the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, the Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque, the National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC, the Roswell Museum, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The 2023-2024 Roswell Museum exhibition Patrociño Barela: I Stand On My Own Feet is dedicated not only to the artist Barela, but also to Edward Gonzales and David L. Witt. Without the immense thoughtfulness, research, and effort they poured into creating the 1996 book Spirit Ascendant: The Art & Life of Patrociño Barela and the subsequent traveling exhibition, this 2023-2024 exhibition at the Roswell Museum would not have been possible. We are sincerely appreciative of the many years they poured into preserving Barela’s rightful place in history during their work in the 1990s and beyond. As an exhibition, Spirit Ascendant traveled 1996-1998 to the Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, the Roswell Museum, the Snite Museum at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, the Albuquerque Museum, and the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos. Independently, Gonzales and Witt each started researching Barela around 1980. They started working together on Spirit Ascendant in 1992. Edward Gonzales is a native New Mexican and a working artist who holds a baccalaureate degree in Fine Arts and a masters degree in Public Administration. He is past chairman of the Organization of Hispanic Artists. His paintings have been widely exhibited in the West. A painting he did of Barela in 1982 has become a widely known image. In Spirit Ascendant Gonzales explains his background in art and how he became fascinated with Barela: “Throughout my youth I loved art. I started to draw and paint at an early age and my teachers, classmates and neighborhood perceived me as having a talent for drawing… My passion for art continued into middle school. By that time I was an avid reader of art books. The public library was a place I spent many hours, gleaning over books on artists. So when we were first introduced to the middle school library I went straight for the art section, looking for books I had not already read. Under the B’s, I found the first edition of a little booklet by Crews, et. al., entitled Patrocinio Barela Taos Woodcarver. The year was 1959 and I was twelve years old. It was an emotionally charged moment. For the first time I found an important artist who did not come from the outer limits. The wonderfully carved figures were at once as sophisticated as Picasso’s and as powerfully executed as the mysterious works of ancient cultures. For that moment I held Barela and his artwork in the highest regard. As an adult my interest in art history continued. I became a painter and graphic artist and my appreciation and admiration for Patrociño Barela never waned. From black and white archival photographs I painted a commemorative portrait of Barela in 1980 (Albuquerque Museum permanent collection) and another in 1989 which was reproduced as a poster to announce the 1990 National Association of Chicano Studies Conference held in Albuquerque, New Mexico in March of that year… In 1980, I had the privilege of meeting David Witt, curator of the Harwood Foundation in Taos.” David L. Witt was Curator at the University of New Mexico’s Harwood Foundation 1979-2005. He is past president of the New Mexico Association of Museums and founder of a national professional group, the Southwest Art History Council. His book, Taos Moderns: Art of the New, (Red Crane Books, Santa Fe) was a winner of the Border Regional Library Association’s 1993 Southwest Book Award. He organized a Barela retrospective at the Harwood Foundation in 1982.

Edward R. Gonzales, Patrociño Barela (after Prather), Circa 1981, Acrylic on Canvas, Courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum, Museum Purchase, 1983 General Obligation Bonds, PC1985.15.1

As the beginning of a series of exhibitions exploring the output of groundbreaking artists who made significant artistic contributions to our region, the Roswell Museum’s 2023-2024 exhibition Patrociño Barela: I Stand On My Own Feet marks a renewed dedication to collaborating with regional peer institutions. Included in the exhibition are the two works by Barela in the Roswell Museum’s collection. We are deeply grateful to the Albuquerque Museum, the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, and the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque for generously loaning to us several additional Barela sculptures as well as painted portraits of Barela by other artists for this exhibition. We hope this effort and collaboration will help the collections of regional peer institutions to reach new audiences and create new opportunities for dialogue with our community here in Roswell.

Curated by Aaron Wilder